Click here to read part 1 of this story.

After the discovery of Langford’s body in the woods of Kentucky and their escape from the Danville jail, Micajah and Wiley Harpe returned to the borderland and continued their reign of terror. It was said that they routinely, “stole secretly to the cabin, slaughtered its inhabitants, and burned their dwelling-while the farmer who left his house by day, returned to witness the dying agonies of his wife and children, and the conflagration of his possessions.” A young negro boy, on his way to the mill with a bag of corn, was later found with his brains knocked out, his grain and horse untouched.1 A traveler named Bradbury was found dead along the road near Southwest Point (modern day Kingston, TN).2

The Harpes assaulted brothers James and Robert Brasel on the Kentucky Trace in Morgan County, Tennessee near Emory River. Robert Brasel made his escape and searched for the group that they were travelling with. Upon returning to the spot, they found James Brasel tied to a tree bludgeoned to death and his throat cut. His rifle had been smashed to pieces and the money in his pocket untouched. Robert Brasel and the party later saw the Harpes camped along the trace with a load of plunder that they had stolen since killing James. Robert Brasel’s small party only had one gun among them, and noticing that the Harpes were well armed, did not attack them. The Harpes and their wives rode into Kentucky and murdered John Tully near the home of Thomas Stockton in Stockton Valley and a youth named Trabeau somewhere further west.3

After these murders, efforts increased to bring Micajah and Wiley Harpe to justice. When news reached Knoxville of their latest crimes, the citizens of the city offered $450 to anyone who could subdue them and bring them to the Knox County Jail.4 On August 15, 1799, the justice of the peace for Green County published an account of James Brasel’s murder in the Kentucky Gazette and described Micajah Harpe as, “pale, dark, swarthy, bushy hair, (his rifle) had a reddish gun stock” while Wiley was armed with a rifle that, “had a blackish gun stock, with a silver star with four straight points.” They were each dressed in, “short sailors coats, very dirty, and grey great coats.” Because of their size difference, Micajah was referred to as “Big Harpe” and Wiley as “Little Harpe.” It was known that both of the Harpes often had to leave their wives behind while on these murderous escapades, but their whereabouts are never discussed in period sources. Except for the one homestead along Beaver Creek near Knoxville, it appears that the Harpe family never lived anywhere permanently, but instead camped in the woods and “rock houses” that dotted the rugged landscape they haunted.5

In August of 1799 the Harpes crossed into Kentucky and murdered a man named Love, a Mr. Stump, and two unidentified men on Roberson’s Lick.6 On August 22, they came to the home of Moses Stegal located on the Pond River. The Stegal family knew who the Harpes were and Moses Stegal was known to be a man of bad character. The Harpes instructed the Stegals, with murderous threats no doubt, to never use their real names in the presence of others.7

Sources vary on how the Harpes came to murder the Stegal family. Judge Hall, an early chronicler of frontier Kentucky, described how Wiley and Micajah Harpe targeted two travelers at the Stegal home, and while impersonating circuit riding Methodist Ministers, murdered the nameless victims in their sleep. Tennessee Historian J.W.M. Breazeale told of how the Harpes arrived at the Stegal home and asked Mrs. Stegal for breakfast. Her husband being away, Mrs. Stegal said that she would feed them if she had someone to watch her baby. The fiends rocked the cradle while the lady cooked the meal. Mrs. Stegal went to check on her child as the Harpes were eating and let out a blood curdling scream. She found her infant drowning in its own blood with its throat cut. Always rewarding kindness with tragedy, the Harpes killed her with the same butcher knife. No matter what transpired before hand, the Harpes burned the Stegal family home with the family inside to cover up this latest crime and, under the cover of a heavy rain, disappeared into the wilderness.8

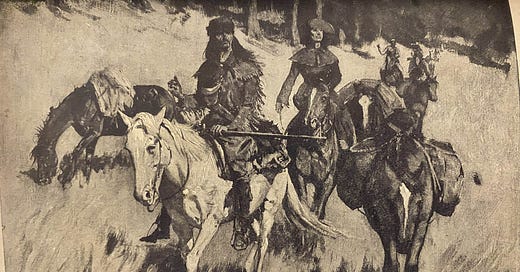

A man named Williams was employed at the Stegal farm to break flax, an important step in the frontier art of making linen for clothing, and hearing the struggle at the house raised an alarm in the neighborhood. He returned back to the home with Moses Stegal and others to find the smoldering ruins of the cabin with the family remains inside. Williams, Stegal, and Thomas Leiper formed a posse and pursued the Harpe brothers into the wilderness. They found the Harpe family camped under a rock shelter around noon the following day. They quietly approached and drew their rifles to fire, and the Harpe brothers scattered like bees from a hive, leaving their wives behind.9 Micajah Harpe, wounded by a rifle ball, mounted a horse and split from Wiley.

The small party left a couple of guards with the Harpe women and the rest continued on. The guards gathered the ladies and tied them by their hands to a couple of small saplings and rode on. Leiper, Stegal, and Williams, reluctant to separate, chose “Big” Micajah Harpe as their prey. Riding at full speed through woods and thickets, Leiper’s steed was never far behind Harpe’s. Leiper pursued Harpe for six or eight miles and finally gained on him. Thomas Leiper was wary to approach Big Harpe as his companions were far behind. Leiper rode closer and fired his rifle, the bullet breaking Harpe’s arm and exiting out of his ribs.10 Harpe took aim, but his gun misfired before he fell from his horse and retreated behind a log. Leiper reloaded his rifle and cautiously approached the wounded man. Harpe, weak from the loss of blood, rushed him with his knife and tomahawk but Thomas Leiper overpowered him, throwing him to the ground. The powerful Micajah Harpe, formerly the scourge of the frontier, now lay defeated. When told that Moses Stegal was soon approaching, Harpe replied, “then I am a dead man.”11

Presenting the bore of his gun to the man’s chest, Thomas Leiper questioned Micajah Harpe as to the reason for his murderous rampage. He replied that he and Wiley, “had become disgusted with all mankind, and agreed with each other, to destroy as many persons as they could. He knew…that he must die some day…but he determined to risk the consequences, and slay as many as he could, before the sword of justice should overtake him.”12 He confessed to killing 17 or 18 people, including many that hadn’t been known previously.13 Of all of the murders, he only regretted one, the murder of his own child. The infant wouldn’t stop crying and he killed it, stating that “I had always told the the women, I would have no crying about me.” Leiper endeavored to extract a whole account of the atrocities caused by the Harpe brothers, but was interrupted by the approach of the posse led by a bloodthirsty Moses Stegal.14

Stegal approached and took Harpe’s butcher knife from Thomas Leiper. Like David with Goliath’s sword, he grabbed Harpe by the hair and drew the knife slowly along the back of his neck. Micajah Harpe stared straight at Moses Stegal, and with a devilish look on his face, said, “you are a God damned rough butcher, but cut on and be damned.” Slicing to the bone, Stegal wrung off Harpe’s head, putting an end to the frontier’s most savage butcher.15

Leiper and Stegal placed the head into a bag and rode back the next morning to where the Harpe women had been left tied up. Leiper interrogated the women about their lives with the Harpes. The wife of Wiley Harpe was “a decent female, of delicate, prepossessing appearance,” and declared that the brothers kept their true character hidden until it was too late. Appalled after the first murder that they committed, she tried to escape but was prevented. She related how she had attempted to escape several times after that. Threats were made that if any of the women left that they and their relations would be brutally murdered. The women also confirmed the confession of Micajah Harpe and described how the men had murdered their own children. The Harpe women were taken back into the Kentucky settlements where they sought protection. The wife of Wiley Harpe wrote to her father who soon took her home, the other two lived the rest of their days in Kentucky. All of the women died in obscurity, and little is known of their later lives.16

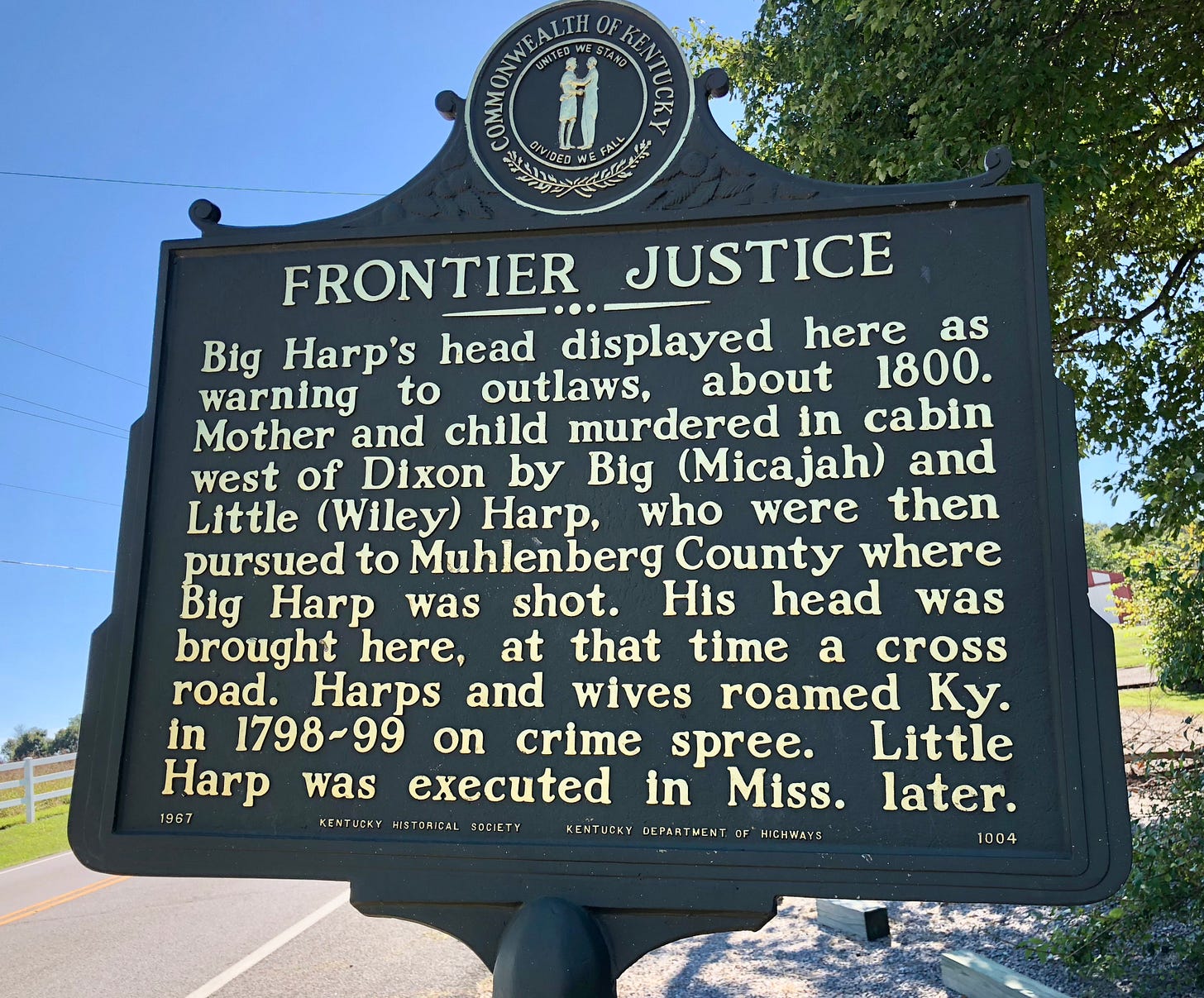

The area where Micajah Harpe was killed was a remote area known as the Green River country. Few settlements were found in this section, which was bordered by Indian land on the south and west. The party stopped at a small farm to purchase some green corn to eat as they camped in the wilderness. Having no where else to store the grain, it was thrown into the bag containing Harpe’s bloody head. Upon stopping for the night, Williams refused to eat any of the corn and endured hunger pangs until they returned to the settlement. Williams, Thomas Leiper, and Moses Stegal rode to a Justice of the Peace in Union County where the head was identified as that of Micajah Harpe. The men rode to the crossroads near Highland Lick and placed the grotesque trophy into the fork of a tree as a warning to other wrongdoers, forever changing the name of the highway to Harpes Head Road. Thomas Leiper was awarded $250 for his “bold and chivalrous conduct” to end the life of Micajah Harpe.17 Little Wiley Harp escaped the fate of his compatriot and fled to the Spanish territory near Natchez, Mississippi and joined the gang of pirate Samuel Mason.

To be continued…

Hall, p.269-270

Breazeale, p.142

"Harp Brothers Murder" Newspapers.com. Kentucky Gazette, August 15, 1799. https://newscomse.newspapers.com/article/kentucky-gazette-harp-brothers-murder/158950231/. Breazeale, p.141-143

"Harp Reward In Knoxville" Newspapers.com. Weekly Knoxville Gazette, August 7, 1799. https://newscomse.newspapers.com/article/weekly-knoxville-gazette-harp-reward-in/158950399/.

Hall p.271 and Breazeale p.143

Breazeale 143 and Lexington Newspaper

Breazeale p.143, Hall p.272

Hall p.272-273, Breazeale p.143-144

Breazeale p.148-149

Breazeale p. 145

Hall p.276

Breazeale p.146

Lexington newspaper and Breazeale p.146

Hall p.277, Breazeale p.146

Breazeale p.146-147

Hall p.280-281, Breazeale 148-150

Hall p. 278, 281; Breazeale 147-150