A Dark And Bloody Ground: Part 3

River Pirates, Three Severed Heads, and the End of Wiley Harpe

Click here to read Parts 1 & 2 of this story

In September of 1799, Little Wiley Harpe mounted his horse and disappeared into the wilderness around Green River, Kentucky. Doing so, he left his murderous partner to the mercy of a mob and ended the early frontier’s greatest nightmare. Yet his story continues in the wild country along the Mississippi River with a patriot turned pirate named Captain Samuel Mason.

Samuel Mason was born in Virginia around 1750 and served as a captain of a Virginia Militia company in the American Revolution. After personally leading an attack on some Indians near present day Wheeling, West Virginia, the official report stated that “this brave young man will no doubt meet a reward adequate to his merit.” Mason was severely wounded in the attack, but forever cemented himself as a brave and daring fighter.1

By 1790. Captain Mason had moved westward to the country south of Green River, near the spot where the Harpes’ final stand took place. At this time, he seemed to be a respectable citizen and signed a petition with other settlers asking the General Assembly of Virginia to create a new county seat. Mason and his neighbors were forced to travel almost two hundred miles back to civilization to conduct necessary business and were “exposed to much danger in traveling through an uninhabited country…(from) high waters, enemies near our frontiers, or other causes.”2 Yet Mason could not be bothered with civilization for too long. By 1794, he and his family had removed to Red Banks on the Ohio River, a place described as “a refuge, not for the oppressed, but for all the horse thieves, rogues, and outlaws that have been able to effect their escape from justice in the neighboring states…neither law nor gospel has been able to reach (t)here as yet.”3

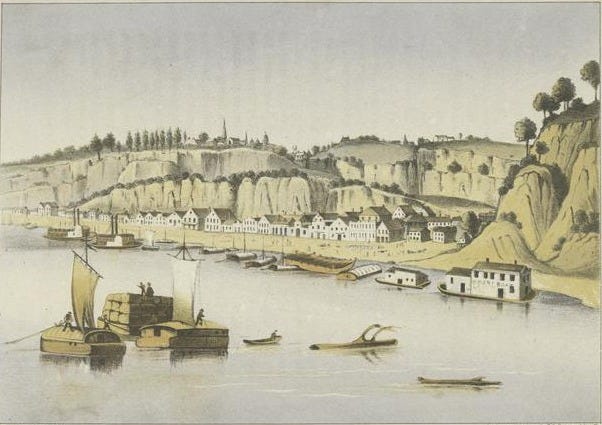

Captain Mason moved his gang of outlaws to the Ohio River by 1797 to take advantage of the booming river trade.4 The Cumberland, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers were the interstate system of the early republic and were responsible for the economic growth of the western frontier. Hundreds of barges, flatboats, and rafts drifted downriver to Spanish New Orleans loaded with farm produce, hogs, cotton, animal furs, and whiskey. When the ornithologist John James Audubon passed through the area almost twenty years later, he found that, “The name of Mason is still familiar to many of the navigators of the Lower Ohio and Mississippi. (H)e issued to stop the flatboats, and rifle them of such provisions and other articles as he and his party needed…His depredations became the talk of the whole western country…The horses, the negroes, and the cargoes, his gang carried off and sold.”5 Mason chose a large cave on the Ohio as a base for his operations and began outfitting it as an inn to lure in unsuspecting travelers. Mason adopted the alias Samuel Wilson and erected a sign on the riverbank advertising “Wilson’s Liquor Vault and House for Entertainment.” Mason’s hideout was known as Cave-Inn-Rock, but the scheme was too obvious, and soon men were dispatched to exterminate the pirates on the river. He abandoned Cave-In-Rock and moved south toward the Spanish territory along the Mississippi River.6 Captain Mason, appeared in New Madrid (in present day Missouri) and applied for a Spanish passport. Doing so allowed him to purchase land in the Spanish territory that would become the Louisiana Purchase, and was the first step to gain Spanish citizenship. By targeting only American boats, and with Spanish control of trade on the Mississippi, Mason practically had a free license to rob and plunder at will.7

It was at this point that he shifted focus from being a river pirate to a land pirate. When Mason’s gang seized a boat going downriver, they had to sell the products and dispose of the evidence themselves. Why not target the travelers as they ventured back home from New Orleans with the cash in their pockets? Watching the loaded boats floating lazily downstream, Mason often exclaimed, “These people are taking produce to market for me.”8 After selling their goods in New Orleans, the raftsmen traveling on the river would abandon their boats and return home via the Natchez Trace, their money and trade goods in tow. The Natchez Trace, a 500 mile wagon track that snaked from Natchez in Spanish Mississippi to Nashville, Tennessee. was used by peddlers, traders, Indians, settlers, ministers, farmers, mail couriers, and rogues to conduct business. With this in mind, Mason began holding up travelers on the trace.

It was here, in the spring of 1802, that Little Wiley Harpe joined the gang of Captain Samuel Mason using the alias John Setton, among others.9 Not long after, the Governor of the Mississippi Territory began a campaign to crush the pirates and wrote to Colonel Daniel Burnett:

“Sir, — I have received information that a set of pirates and robbers who alternately infest the Mississippi River and the road leading from this district to Tennessee…a certain Samuel Mason and a man by the name of Harp, are said to be the leaders of this banditti…These men must be arrested; the honor of our country, the interest of society, and the feelings of humanity, proclaim that it is time to stop their career; The crimes of Harp, are many and great, and in point of baseness, Mason is nearly as celebrated…If you should fall in with Mason and his party you will use all the means in your power to arrest them…I hope that the honor of taking these lawless men, will be conferred upon the citizens of your neighborhood; should they succeed, I promise them a very generous reward.10

Wiley Harpe’s whereabouts between the time of Micajah’s death and his joining the Mason gang are unknown, but Territorial Governor Claiborne’s public condemnation of he and Mason was a calculated choice. By connecting Mason’s crimes with the presence of Wiley Harpe, he put the settlers on high alert and gave them incentive to capture the gang. Governor Claiborne offered $900 for the capture of Samuel Mason and Wiley Harpe.11 Indians and settlers alike began hunting for Mason’s gang, and he fled across the river to Spanish territory to hide. After capturing a traveler who was carrying a copy of the governor’s proclamation, Mason read it aloud to his gang and “indulged in much merriment on the occasion.”12 Yet it was not an Indian band, vigilante party, or militia company that he would have to worry about, but the people that he trusted around him.

In January of 1803, Mason was trapped and arrested by Spanish authorities near New Madrid in connection with crimes that happened on their side of the Mississippi River. He and his gang (which included four of his sons, a daughter in law, three grandchildren, and Harpe) were taken to New Madrid to stand trial. Proving that there is no trust among thieves, Mason began implicating the members of his gang, including Wiley Harpe (alias John Setton) for all of the crimes that he was accused of. Setton was brought forward and asked what association he had with the man named Harpe and he replied that “he had met a man by that name in Cumberland who had since been killed, but had left a brother, whose whereabouts was unknown to him…but he felt confident that Harpe had not been around since he had had the misfortune to fall into Mason’s hands.” Setton turned on Mason and claimed that the Mason gang had taken him prisoner and kept him for menial jobs and petty crimes. Spanish authorities searched through the saddle bags captured with the Mason gang and found “twenty twists of human hair of different shades which do not seem to have been cut off voluntarily by those to whom the hair belonged,” several guns, and seven thousand dollars in paper notes and silver. After considerable back and forth between the Mason family, John Setton, and numerous other witnesses, Mason was found innocent of any crimes in Spanish territory, but openly confessed to numerous crimes in U.S. territory. The authorities ordered the whole gang taken to New Orleans and extradited to the United States.13

The prisoners were taken on a boat for the nine hundred mile trip downriver to New Orleans. It is likely that Setton (Harpe) was kept separate from the rest of the gang in hopes that he would turn state’s evidence against Mason and implicate other outlaws who were active on the river. He was described as having “a suspicious exterior…about thirty years of age and looked…too much of a villain to smile and thereby try to hide some of his villainy.”14 Upon reaching the city, the Spanish authorities sent the prisoners northward to Natchez to be remanded to the U.S. authorities. The mast of the vessel snapped near Baton Rouge and a detail was sent onshore to hew another one. Finding the vessel lightly guarded, Mason and his gang overpowered the guards and took control of the craft on March 26, 1803. Mason was wounded in the scrape and he disappeared into the swamps surrounding Natchez. Other than some scattered sightings, Mason was never seen again, although roving bands again roamed the wilderness hoping to collect the $1,000 reward that the territorial government advertised for his arrest.15

Soon after two men arrived in Natchez, Mississippi carrying the severed head of the notorious Samuel Mason. The head was recognized by scars and miscellaneous marks as described in the wanted ad, causing quite a stir in the territory. The two men appeared before a magistrate to collect the reward and identified themselves as John Setton and James May, past associates of Samuel Mason’s. Before the money was counted, a man rushed into the courtroom calling for the arrest of the two men, his reasoning being that he recognized the men as two outlaws who had robbed him and killed his companion on the trace two months before. Furthermore, John Setton was recognized by U.S. Army Captain John Stump as being none other than Wiley Harpe. Both men were arrested and promptly placed into jail.16

The news of Harpes’ capture spread like fire through a canebreak, and five boatmen, including two who were witnesses to the Harpes’ escape from the Danville jail, arrived and promptly swore that John Setton was Wiley Harpe. One fellow stated that, “if he is Harpe he has a mole on his neck and two toes grown together on one foot.” Upon finding that his evidence was correct, the witness reportedly wept. John Bowman from Knoxville arrived and told how Wiley Harpe had a scar on his left breast from a stab wound that he inflicted during a fight with Harpe in Tennessee. Bowman tore open the prisoner’s shirt and proudly presented the scar to the authorities.17

Knowing that the jig was up, Harpe and May escaped from Natchez but were recaptured shortly afterwards. They went to trial in January of 1804 in Greenville, Mississippi and were found guilty of highway robbery. Both men were sentenced to be hanged until they were “dead, dead, dead.” On February 8, 1804, Wiley Harpe and James May marched to Gallows Field near Greenville. Harpe made an unrecorded confession on the gallows, May maintained that he had done nothing worthy of death. By four o’clock, each man was dangling in the slight chill of a central Mississippi winter. Afterwards, their heads were severed and placed on poles along the Natchez Trace, serving as grim irony considering their greed to collect the reward on Captain Samuel Mason.18

Reactions of people in Kentucky and Tennessee to the execution of Wiley Harpe are not recorded. The Kentucky Gazette ran this notice near the end of February, “There have been two of Sam Mason’s party — which infested the road between this country and Kentucky — in jail at Greenville for trial. They were condemned last term and executed this day. One of them was James May; the other called himself John Setton but was proved to be the villain who was known by the name of Little or Red-headed Harpe, and who committed so many acts of cruelty in Kentucky.”19 The bodies of Wiley Harpe and James May were cut down and buried in an unmarked grave along the Natchez Trace. By 1850, the road had eroded and widened to the point that the bleached bones were exposed to the elements. They were finally drug away by dogs and other animals, removing the last trace of the wicked Harpe brothers from the earth.20

From 1796 to 1804, Wiley and Micajah Harpe were the early frontier’s worst nightmare. Their crimes were violent and unnecessary, and there were most likely many more atrocities that went unreported due to the unorganized nature of the early settlements. Their known body count numbers eighteen souls, more than the number of victims killed by Jeffrey Dahmer. And while their names have been replaced by other serial killers who appeared later in the 19th century such as H. H. Holmes and Jack the Ripper, their career illustrates the dangerous nature of life on the frontier. The two Harpe Brothers serve as a startling revelation of the level of violence that Europeans could inflict on each other in a time when the American Indian was viewed as a savage beast that should be removed from the landscape. This shows that not everyone who ventured west went there for a noble reason. Many were looking for any excuse to rob and kill and found that the frontier was an easy place to hide.

A list of their known victims follows below.

Coffey youth

— Johnson

— Ballard

— Peyton

Stephen Langford

Young African American male

— Bradbury

James Brasel

John Tully

Trabeau youth

— Love

— Stump

Two unidentified travelers on Roberson’s Lick

Mrs. Moses Stegal

Stegal infant

Harpe infant

Captain Samuel Mason

Outlaws Of Cave-In-Rock p.158-162

Ibid p.166

Ibid p.167

Ibid p.175

Ibid p.177

Ibid p.175-177

Ibid p.178

Ibid p.176

Ibid p.199, p.256 (To shield his identity and complicate the historical record, Wiley Harpe would use various aliases including John Setton, John Taylor, and Wells during his time with Mason’s pirates.)

Ibid p.196-197

Ibid p.199-200

Ibid p.200-202

Ibid p.209-237

Ibid p.244

Ibid p.251

Ibid p.252-255

Ibid p.255-256

Ibid p. 256-263

Ibid p.262

Ibid p.266