High on the Cumberland Plateau is a town that defies the imagination. While driving through the Tennessee countryside, you come across a Victorian Village that looks like it might have stepped out from a storybook. From the beginning, the colony of Rugby was founded on three things: education, co-operation, and hard work. It was these three principles that Thomas Hughes instilled in his colonists and hoped that they would carry on through the ages. While Rugby has often been cited as a failed Victorian Utopia, or a “town of cultured ghosts”, in reality, the outcome was much different.1 Although the town did not flourish into what Hughes had planned, these founding principles lived on through the villagers who clung to this town on the plateau and through the lives of the colonists who ventured beyond the Cumberland Plateau into the rest of the United States.

Rugby was founded in 1880 by Thomas Hughes. Hughes was an Oxford educated lawyer, judge, member of parliament and Queen Victoria’s council, social reformer, athlete, and author. A friend once stated that he had seven times more irons in the fire, and that he heated them seven times hotter than anyone else.2 Of all the things that Hughes had done in his lifetime, he was most well-known for his writing, although he did not aspire to be a writer. He wrote the manuscript of his most famous novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays for his son Maurice who was going away to Rugby school in England. A family friend came to his house and after reading through the manuscript, declared that it should be published. Hughes and his friends began looking for a publisher and Hughes wrote to MacMillan Co. that, “I have the book that will make your fortune.”3 MacMillan began publishing the book, and within the first year there were six editions. From 1857-1862, his novel sold 28,000 copies, and would be MacMillan’s first million selling book by 1900. It was one of two books personally endorsed by President Theodore Roosevelt as a book that all boys should read.4 As of this writing, the book has never been out of print. The book has been translated into French, German, Hebrew, and Japanese, among other languages. It has been adapted for the silver screen several times, the earliest being in 1916.

The reason that this book was so popular is that it was the first time that a child was the main character in a novel. Although Tom Brown’s Schooldays has a moral twist to it, it served as an early taste of modern children’s literature. This work no doubt influenced Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, Little Women, and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. This book has been recently re-imagined into the popular Harry Potter series, and shares many of the same themes as the modern counterpart. The popularity of this book made Hughes into a celebrity, and he toured Britain and the United States talking about his work. It was through his popularity that he was able to recruit people to come to his colony in Tennessee.

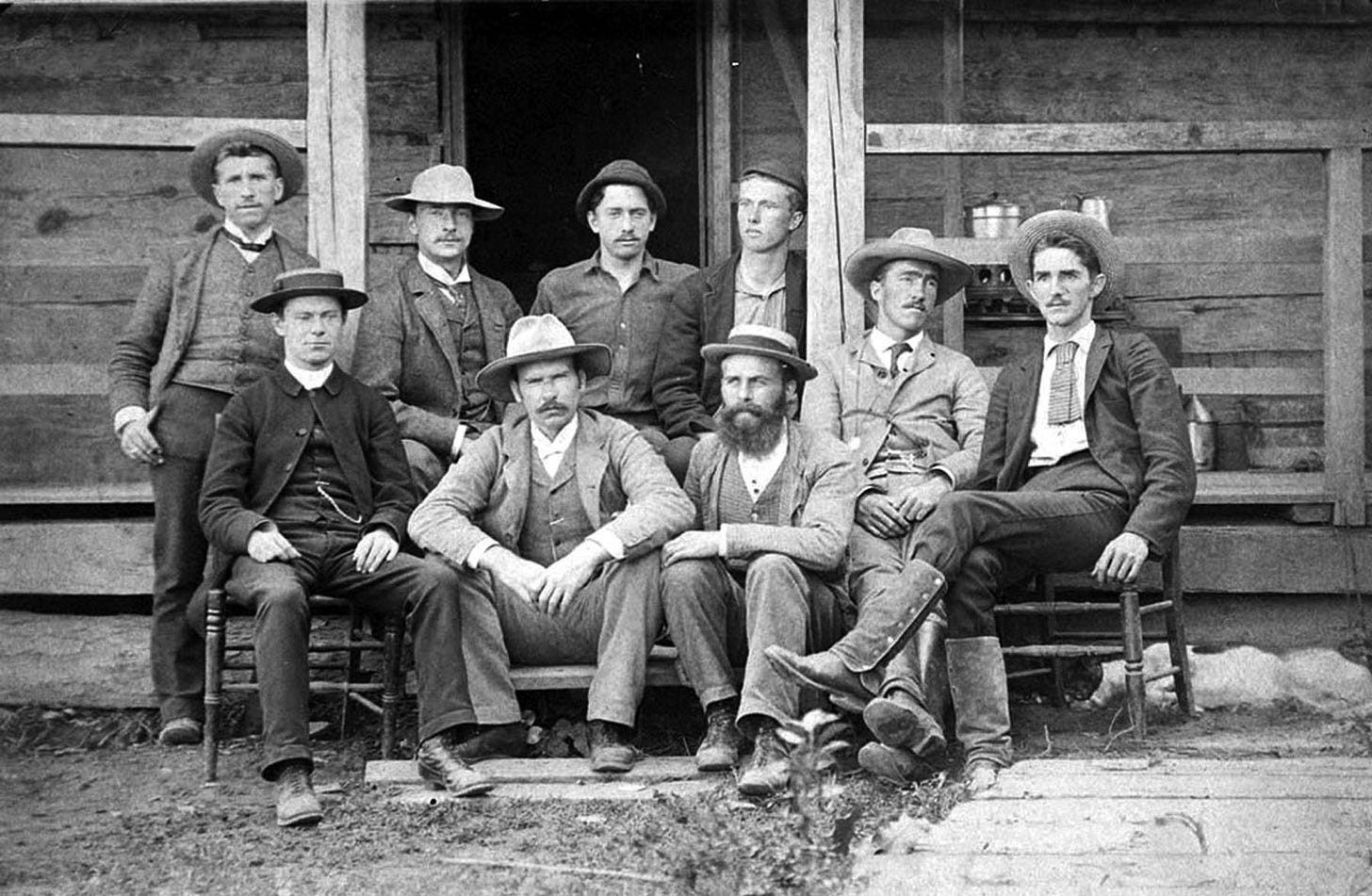

Hughes founded Rugby as a colony for the second sons of the English gentry. English law since the medieval period allowed that the eldest son would inherit the estate when the father died. Younger sons, all called second sons, were given an allowance or a lump sum, but were otherwise left to find their own place in the world. These second sons were expected to work for a living and were only allowed to fill white collar positions; namely, army officers, clergymen, doctors, and lawyers. In the late 1800s, the job market was flooded with people who were qualified to fill these positions, but there were not enough jobs to offer to everyone. Hughes saw how the talent that these young men had was being wasted, so he created a place where these gentlemen could pursue careers that were not open to them in England, such as farmers, merchants, and craftsmen. Hughes had looked for other places to put his colony, but he finally decided on the Cumberland Plateau in East Tennessee because the land was mostly undeveloped, and the United States has always been viewed as the land of opportunity. Without the stigma that these enterprising individuals would face in England, they were open to pursuing whatever career they pleased.5

But was Rugby a failure? After Margaret Hughes died on October 5, 1887, Thomas Hughes never returned, and newspapers immediately called the town a failure. Monetarily, Rugby was a huge failure. Thomas Hughes had invested most of his fortune gained from his books into the venture and he lost it all. When he returned to London, he had to sell his house in the city and buy a smaller house in the country. Instead of being able to retire to his Tennessee colony, he had to take a job as a county judge to make ends meet. When Hughes died in 1896, he had lost $1,000,000 on Rugby.6

Although many of the original colonists did not stay in the village, the venture cannot be called a failure until you look at the lives of the people who were touched by this venture. A few, like Englishman Arthur Churchill (Winston Churchill’s first cousin) returned to England, but they had the opportunity to try out life in America. After coming to Rugby, many of the second sons decided to stay in the United States, like Charles Jefferson, who became an inventor for Edison Electric Works. Arthur Dyer, another young Englishman, invented micanite insulation, an industrial thermal insulation still used today. Graham Egerton arrived in Rugby with a letter of introduction from Thomas Hughes and wanted to study medicine. After losing his arm in a railroad accident, he entered civil service and became legal representative for the naval office under President Woodrow Wilson.7 Reverend Joseph Blacklock, the first minister of Christ Church Episcopal, moved with his five sons to South Pittsburg, TN and became involved in the Blacklock Foundry, which was later changed to Lodge Cast iron, the world’s largest manufacturer of cast iron cookware to this date.8 Although Hughes wished that these colonists would have stayed and made their life in Rugby, they were still successful in pursuing jobs that were not open to them in England.

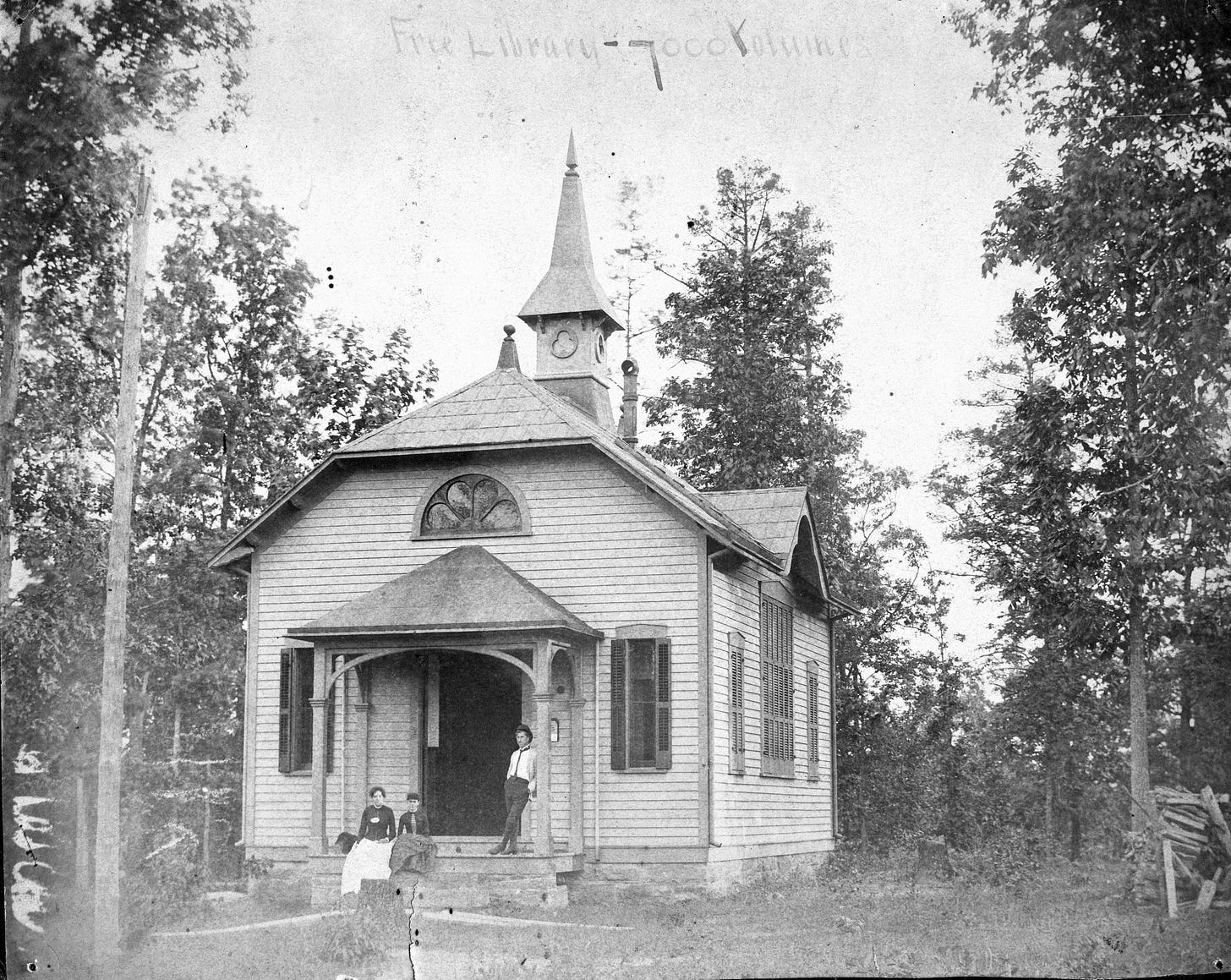

Some of the colonists did stay, such as Ernest Alexander, who was the last of the original colonists living in Rugby when he died in 1956 at 96 years old. The fact that Rugby was not a failure is substantiated by the buildings that are left. Books were being checked out of the Hughes Library until the 1950s when the school positioned next door to the library closed and was consolidated. The homes and other buildings that survived only did so because there was someone there who took care of them. The descendants of original colonists, local families, and new residents all moved in to take care of the buildings that were left until the restoration could begin in 1966. Residents of Rugby today still work together in co-operative efforts to take care of hiking trails, restore buildings, put out fires, make quilts, among other activities.

Lastly, although Thomas Hughes lost most of his fortune on the venture, he was not disheartened. In his last letter to the colony, addressed to the students at the one room school in Rugby, he stated, “I can’t help but feeling and believing that good seed was sown when Rugby was founded...and that someday the reapers, whoever they might be, will come along with joy, bearing heavy sheaves with them.” Therefore, as long as anyone living or visiting the colony continues in the spirit of education, co-operation, and hard work, then they are perpetuating the success of Rugby into the 21st century.

For more information about Rugby, visit their website at www.historicrugby.org.

“Town of Cultured Ghosts”, Holiday Magazine 1948

As quoted from the Hughes exhibit in the Rugby Schoolhouse

As paraphrased from the Hughes biography by Mack and Armytage

“The American Boy” by Theodore Roosevelt. A German copy and Hebrew copy are in the Rugby Archives.

Much information about the book can be found in the Hughes biography by Mack and Armytage and internet articles about the book

“A Castle In The Wilderness: Rugby Colony, Tennessee, 1880-1887 by Margaret McGehee in “The Journal of East Tennessee History” 1998. In her introduction to the updated version of Rugby, Tennessee by UT Press, Dr. Benita Howell stated in citation number 33 that Hughes lost $750,000 as of 2005. I went to the same website that she used to calculate her figure and updated it for 2020. It puts it at almost $1,000,000 in 2020 currency.

This information can be found in Distant Eden by Brian Stagg and the interview with Graham Higgs on the Historic Rugby Facebook page.

Christ Church South Pittsburg, Tennessee First 100 Years by William Jackson Wilson p.27-28