Final Recognition

How two United States soldiers received the nation's highest honor, 162 years after their death.

In a larger sense, we can not dedicate -- we can not consecrate -- we can not hallow -- this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it…It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us -- that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion -- that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain…

The Gettysburg Address

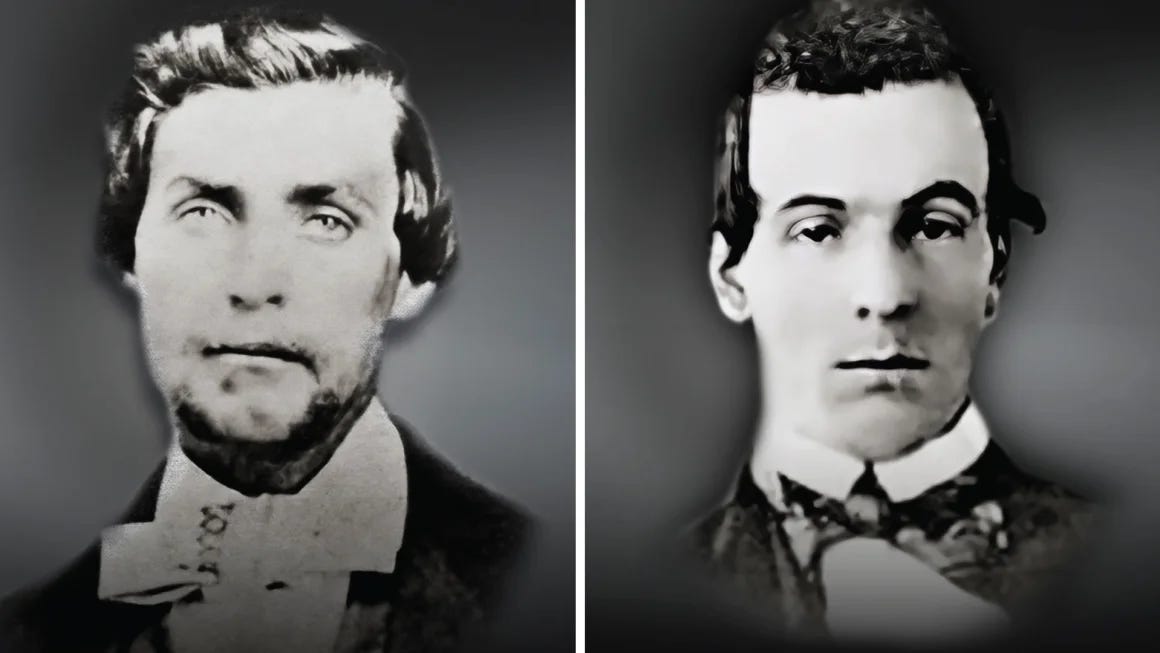

On July 3, 2023, two soldiers who were executed in their country’s service received the highest honor that the United States can bestow, 160 years after their death. Privates Charles P. Shadrach and George Wilson of the 2nd Ohio Infantry were part of a covert group specially selected to harass the Confederate interior and have now joined their comrades in receiving the Medal of Honor.

The Civil War was not going well for the Union in 1862. After the victories of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson on the Tennessee River, the Union occupied Middle Tennessee and General Ormsby Mitchel began moving eastward toward Chattanooga. At the suggestion of spy James Andrews, General Mitchel approved a daring plan that would send a squad of soldiers behind enemy lines to hijack a locomotive and tear up railroad track, burn bridges, and cut telegraph lines, opening the way for a Union invasion into the deep south. Andrews was appointed leader of this group and selected twenty-five men to assist with the mission. After being delayed by rain and Confederate patrols, twenty-one men reported for duty in Marietta, Georgia on April 12, 1862. Andrews, Shadrach, Wilson and the rest boarded the General and commandeered the train when the crew stopped for breakfast at Kennesaw. Uncoupling the passenger cars, they traveled north, all the while being pursued by Conductor William Fuller and a skeleton crew of Western and Atlantic Railroad employees. Nearing the Tennessee border and with the General losing steam, all hands abandoned the mission.

Pursued by bloodhounds, every member of the party was captured and imprisoned. Shadrach, Wilson, and several others were court martialed as spies in Knoxville before being returned to Atlanta to face execution. William Pittenger, also from the 2nd Ohio, recalled the morning when Privates Shadrach and Wilson were executed alongside four other soldiers and William Campbell, a civilian who assisted in the operation.

“It was the manner of death rather than death itself which seemed so horrible to our comrades as they took their last leave of us. Most of them were also without any clear hope beyond the grave. A day, even, to have sought Divine favor would have been a priceless boon.

(Perry) Shadrack was careless, generous, and merry, though often excitable, and sometimes profane. Now he turned to us with a forced calmness of voice which was more affecting than a wail of agony, as he said, ‘Boys, I am not prepared to meet my Jesus.’

When asked by some of us, whose tears were flowing fast, to think of heavenly mercy, he answered, still in tones of thrilling calmness, ‘I’ll try. I’ll try, but I know I am not prepared.’”

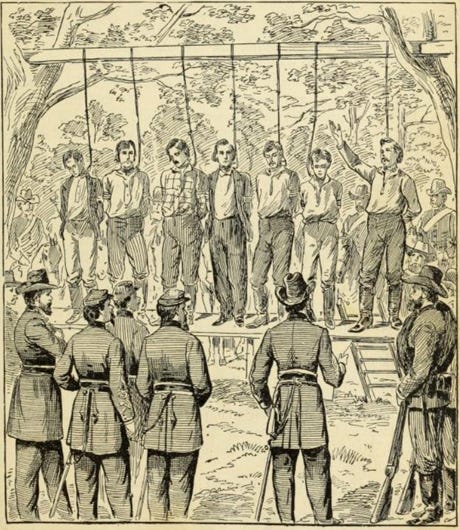

Before being executed, George Wilson addressed the crowd gathered before the gallows:

“Wilson was a born orator, and he now spoke with marvelous skill and persuasive eloquence… He began by telling them that though he was condemned to death as a spy, he was no spy, but simply a soldier in the performance of duty; he said that he did not regret dying for his country, for that was a soldier’s duty, but only the manner of death, which was unbecoming to a soldier…(H)e declared that he had no hard feelings toward the south or her people, with whom he had long been well acquainted; that they were generous and brave; he knew they were fighting for what they believed to be right, but they were terribly deceived. Their leaders had not permitted them to know the facts in the case, and they were bringing blood and destruction upon their section of the nation for a mere delusion... The guilt of the war would rest upon those who had misled the Southern people, and induced them to engage in a causeless and hopeless rebellion. He told them that all whose lives were spared for but a short time would regret the part they had taken in this rebellion, and that the old Union would yet be restored, and the flag of our common country wave over the very ground occupied by this scaffold.”1

The condemned were buried in a shallow grave near the scaffold, close to the grave of their leader James Andrews who was executed a week prior. The surviving “Andrews Raiders” made an attempt to escape prison that summer, but five were recaptured and later exchanged. Upon release, William Pittenger and his comrades travelled to Washington D.C. to update Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and President Abraham Lincoln on their failed mission. While there, they were presented with the newly minted Medal of Honor for their bravery. Upon hearing that several of the men had escaped prison and returned to their units, the War Department made the effort to locate the men and issue them the Medal of Honor. Most of the soldiers who were executed were issued their medals posthumously in 1863, although the family of Samuel Slavens did not receive his commendation until 1883. Philip Shadrach and George Wilson were overlooked until July 3, 2024, when descendants of the two men received the medal from the President of the United States, finally joining their comrades in bearing this honor. Civilians James Andrews, leader of the mission, and William Campbell are not eligible to receive the Medal of Honor.

Private Charles P. Shadrach, Private George Wilson, James Andrews, and the others who were executed now lie in the shadow of a monument honoring their sacrifice at the National Cemetery in Chattanooga, TN.

Interested in reading more about the first Medal of Honor recipients? Check out Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor by Russell S. Bonds.

If you liked this article, please share with someone and ask them to subscribe. The only way that this publication can grow is by gaining readers. Thank you.

William Pittenger, The Great Locomotive Chase: A History of the Andrews Railroad Raid Into Georgia In 1862 (New York, John B. Alden, 1893) p.284-288, accessed through Archive.org